Maxville Logger Company Photo, c.1926

The loggers stand with tools they used daily. The men with long poles and ax’s, scalers, measured the board feet to the standard length, the men with the crosscut saws, sawyers, cut the trees and worked in pairs, usually with someone they knew. Matching your partner was critical to rhythm and speed, the more you cut, more revenue. The men holding bottles with cloth stuck in the neck, kept the saws clean as the men sawed, the bottles contained turpentine that melted the sap. The man holding the stamp in one hand used to mark the felled timber and revolver in the other was the foreman, Don Riggles. His crew respected him for his fair treatment, as told by his daughter Ronee Riggles. TIMBERRR!

Photographer unknown

Delores Crow Smith Collection

Maxville Company Headquarters, c.1925

The Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company ran their business out of this building. Superintendent J.D. McMillan, after whom the town was named, called it home. Unlike other Maxville houses, it had both electricity and indoor plumbing. It also served as a meeting place for Maxville residents. Verne Vezie Church, Chief Clerk, (pictured) is manning the headquarters.

Photographer unknown

May Ann Henderson Collection

Maxville Company Store, c.1925

The main company store provided goods for all of Maxville. The building was manufactured at the local mill in Wallowa and transported to Maxville by train on skids. People would buy large bags or sacks of Flour, sugar and other goods to last a long time.

Photographer unknown

May Ann Henderson Collection

Post Office and Payroll Building, c.1925

In September 1923, the town of Vincent's post office was moved to Maxville. The center of town also boasted a hotel, a doctor's office and the commissary. The hotel -- with sixty rooms, a barber shop and a dining room that sat eighty -- was bought and torn down in the late 1930s and hauled to Troy, where the lumber was used to build a store.

Photographer unknown

May Ann Henderson Collection

They called it Mac’s Town, c.1925

J.D. McMillan was the logging superintendent for the Bowman-Hicks Logging Company. Maxville was the main logging camp he directed and his name was even said to have inspired the town's name. There were very few cars in Wallowa County, yet alone Maxville, but as the superintendent, McMillan had the resources to drive one.

Photographer unknown

Raymond Puckett Collection

Dr. Floyd at Maxville, c.1925

Doctors were provided with contracts by Bowman-Hicks to treat loggers and residents of Maxville. According to Jack Gregory, son of Maxville doctor J.F(old doc) Gregory, they treated injuries sustained in train wrecks and logging accidents, and even set the occasional broken bone resulting from a drunken baseball game. Doctors often got paid with quilts, chickens and other barter.

Photographer unknown

May Ann Henderson Collection

Maxville Bull Cooks Mr. and Mrs. Mc Craven, c. 1925

Eating was taken seriously in Maxville. Loggers ate around 6,000 calories per day just to perform their daily functions. Local ranches and homesteaders sold beef and produce to townspeople and some Maxville residents even raised their own pigs. Men, horses, and steam engines were primary resources for Maxville’s revenue.

Photographer unknown

May Ann Henderson Collection

Maxville’s Segregated Schools, c. 1926

Maxville was mapped according to an often-used template in company towns, one that segregated residents by marital status and ethnicity. In 1926, two buildings, one for white students and one for Black students, were hauled to Maxville. The school for white students was located on the south side of Maxville and taught up to 75 students while the school for Black students was located on the north side of town and taught around 13 students. Maxville's schools were the only segregated schools in Oregon at that time.

Photographer unknown

Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center Collection

Maxville’s Segregated Schools, c. 1926

The school for white students was located on the south side of Maxville and taught up to 75 students while the school for Black students was located on the north side of town and taught around 13 students. Maxville's schools were the only segregated schools in Oregon at that time.

Photographer unknown

Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center Collection

Friendships Say NO to Jim Crow, c. 1937

Despite Bowman-Hicks' enforcement of Jim Crow-inspired segregation mandates, Maxville's isolation from mainstream society encouraged the formation of interracial friendships. Black and white townspeople socialized and often shared resources. When Bowman-Hicks ended its logging operation in 1933, the Black and White schools desegregated and the remaining Maxville children attended school together, taught by Madeline Riggles. Both Black and White loggers from the South, local loggers and homesteaders logged Maxville.

Photographer unknown

Ona Hug Collection, gifted by son, Chuck Bertleson

Washday at Maxville, c. 1924

Part of daily life in Maxville involved doing the wash. Washing was women's work, though men and children might fetch water from the two springs that fed the town. Crew bosses and managers had water pumps in their houses, which doubled as status symbols. This photo shows washing in the white part of town, and it looked different in each area because Maxville was segregated by marital status, ethnicity, class and job. The loggers' overalls were rarely washed -- the pitch (sap) was difficult to remove, and served as fabric-reinforcing resin.

Photographer unknown

Jack Evans Collection

Under Red Water Tower, C. 1926

Water towers were key to running steam driven engines. This one was located South of Maxville. Water was crucial even at 20 below. In the winter months, Maxville residents had to shovel up to five feet of snow to access their outhouse and water. Loggers and their families kept warm despite the long winters that one former resident described as "darn cold." Ray Puckett’s mother under the ice flow.

Photographer unknown

Raymond Puckett Collection

Herschel Jones on Steam Engine, c. 1923

Bowman-Hicks had six locomotives. One of these locomotives was a Shay, which weighed 110 tons. The Shay was gear driven and used on steep grades. It would hook onto twenty loaded double-decker cars and roll down the 6% grade to Vincent, north of Minam along the Grande Ronde River. Here, Shay engineer Herschel Jones had just been promoted by Dan Tanner.

Photographer unknown

Jack Evans Collection

Logging Train Wreck, c.1924

Transporting logs from Maxville to the mill was not always a smooth operation. Train wrecks like this one resulted in several cars and loads of lumber splayed across the tracks. Workers directing the operation would have had to work together -- regardless of race and ethnicity -- to right the situation.

Photographer unknown

May Ann Henderson Collection

Bucking Logs, c.1924

Bucking logs is the process of cutting a felled, limbed tree into logs. The price and requirements for quality and size of logs was determined by their final form, such as plywood, lumber, or pulp. Logs lose value if they are not optimally bucked. Cutting and moving these logs is incredibly difficult work, and was carried out by Maxville loggers year round, including wintertime in several feet of snow. Company jobs were ethnically segregated; Blacks usually felled and cut trees, Greeks had more expertise building railroads, and whites worked as bridge builders, truck drivers, saw filers and tree toppers. Loggers could and would perform several aspects of the job.

Photographer unknown

Raymond Puckett Collection

“Cutting up” on the Job, c. 1923

Because there was no lumber company at Maxville, and trucks were not suitable for moving logs out of the forest, Bowman-Hicks used other means, steam locomotives were used to transport lumber sixteen miles south to Wallowa. In the midst of this hard work in a harsh environment, people found time to express themselves and have fun.

Photographer unknown

Jack Evans Collection

Maxville Baseball, Playing on Even Ground, c.1925

Baseball was an essential pastime for many Maxville residents. Bowman-Hicks' segregation of the town extended to baseball; Maxville had two teams, one Black and one white. The company "had a baseball club in its business model to provide an outlet for workers" and perhaps, to promote an activity that encouraged working toward a common goal. Although they usually played each other on the town's baseball field, the two teams merged when they competed against other local teams -- Wallowa, Joseph, Enterprise, Elgin and La Grande -- and became the Maxville Wildcats. According to a newspaper article, the integrated team "played rings around the other team, scoring at will." To watch a baseball game in 1925, will cost you 35 cents.

Photographer unknown

Lively Collection

Time Out With Friends, c.1925

Babe Janney (right) sits on the lumber railroad tracks accompanied by her friend who came to visit Maxville. These women were probably school friends of Vera Svendsgaard. Vera, was a secretary for Bowman-Hicks.

Photographer unknown

Mae Ann Henderson Collection

Between Chores and School, c.1937

Although the schools were located on opposite sides of Maxville, kids found ways to connect and play. The children pictured went to segregated schools and at the end of the school day founds ways to meet up and forge friendships.

Photographer unknown

Ona Hug Collection, gifted from son, Chuck Bertleson

Playing in the Creek, c.1937

Maxville children devised creative ways to stave off boredom and cool down during the summer. While children were expected to perform household chores, they also found time to hunt, fish and play in the woods and in the local swimming hole.

Photographer unknown

Ona Hug Collection, gifted from son, Chuck Bertleson

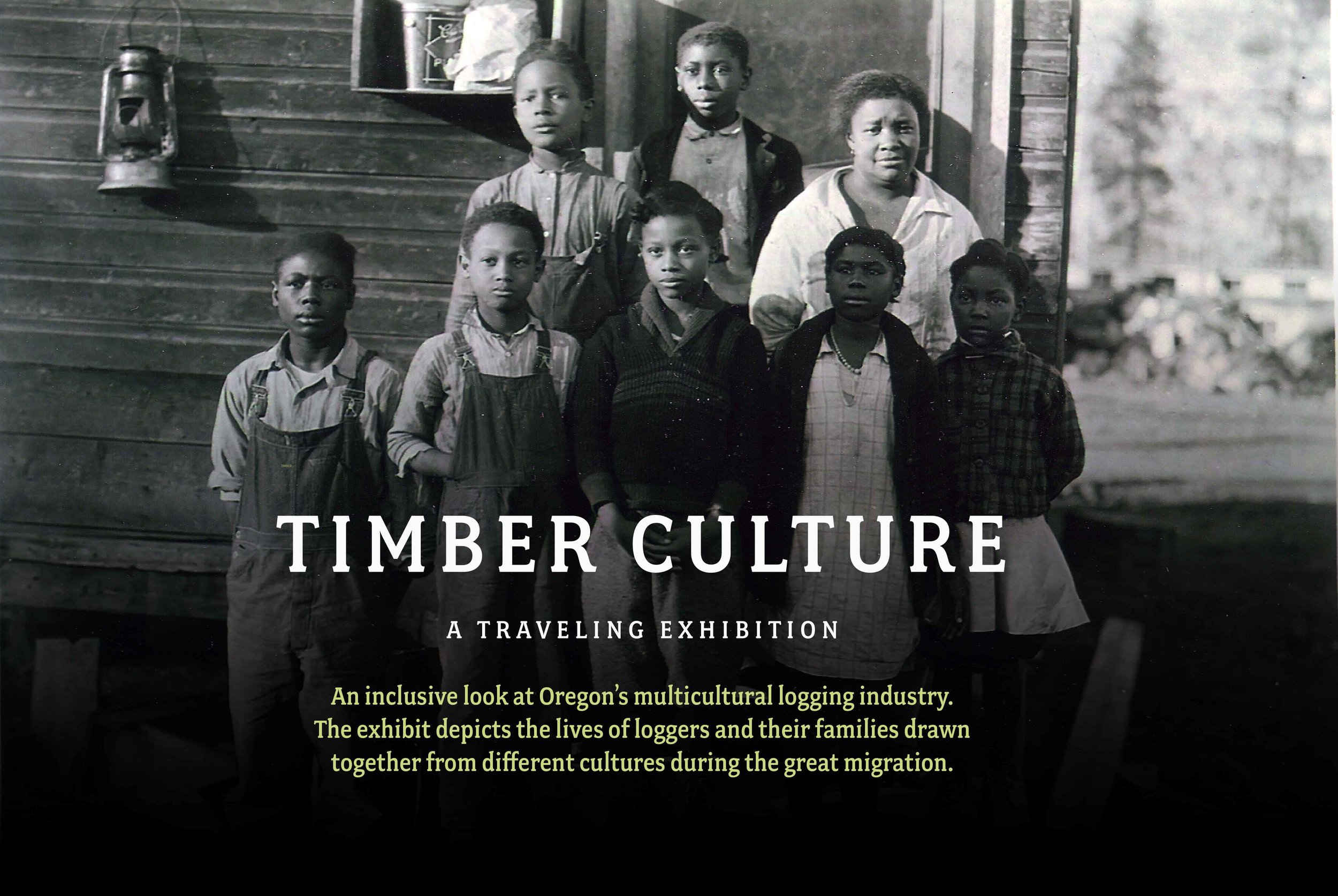

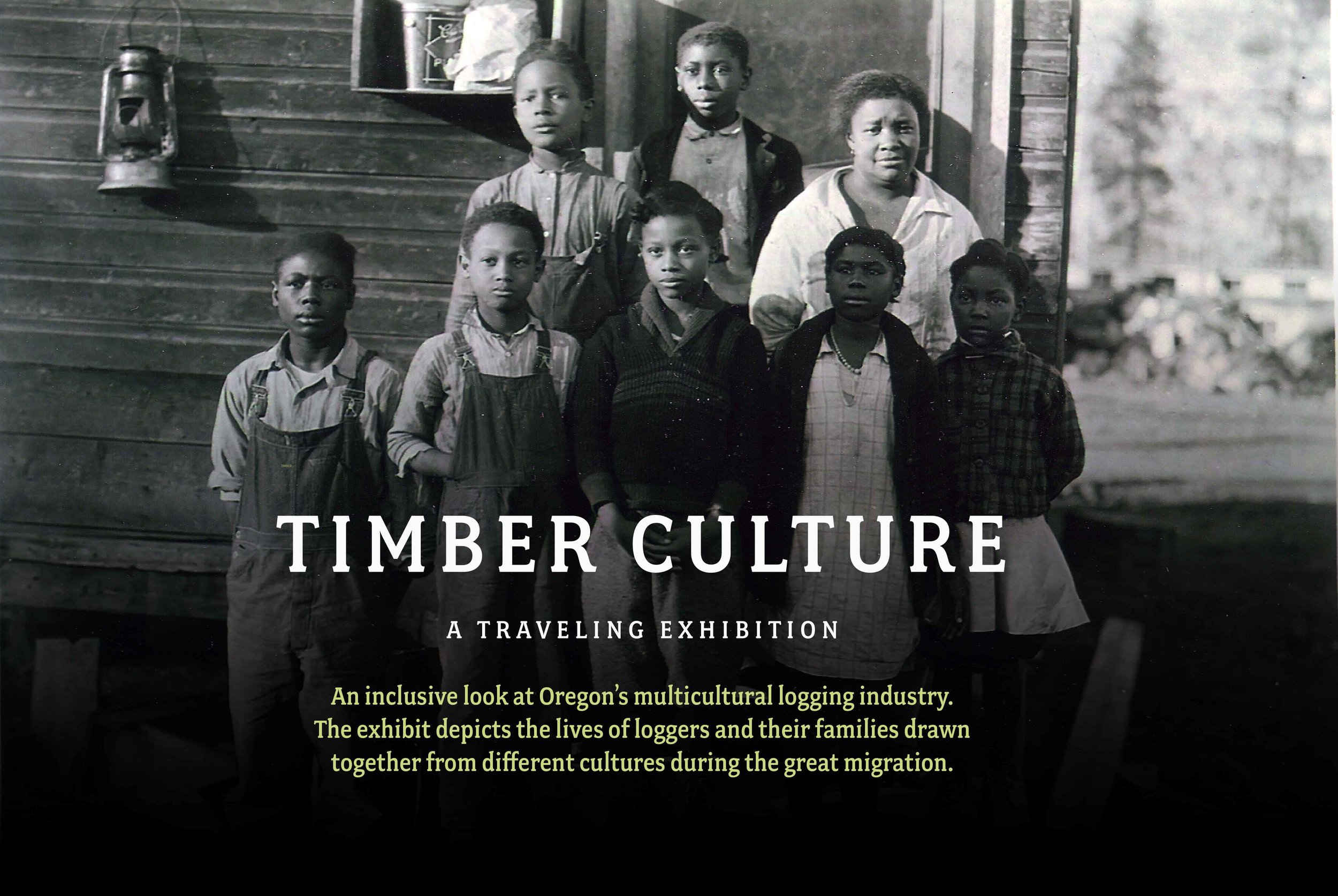

Timber Culture